Your Grandmother’s Wisdom Still Protects You

By Dawn DiPrince, CEO of History Colorado

For me, history is not so much about textbooks and timelines but about ancestors and grandmothers.

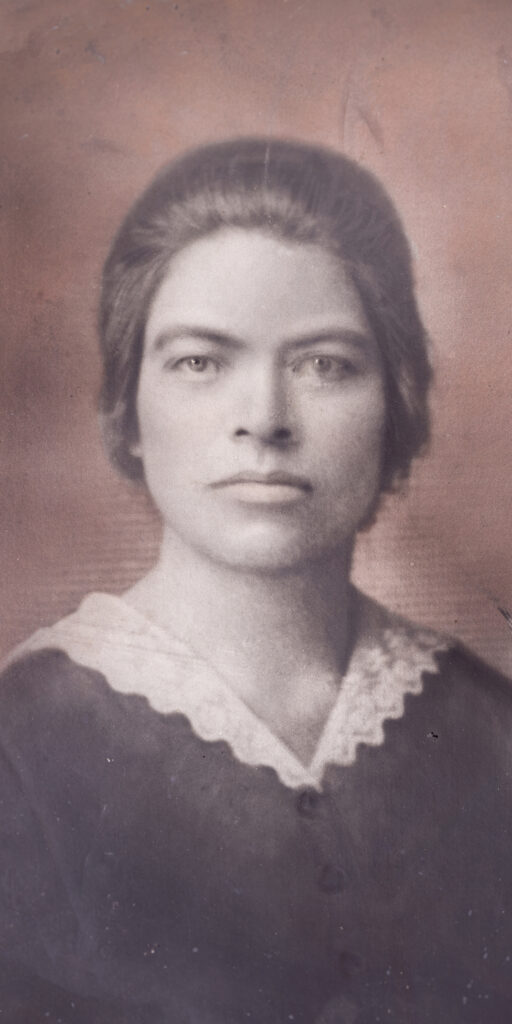

I have a photo in my kitchen of my Grandma Lena, her four sisters, and their mother. My great-grandmother Bettina Trapaglia, who became Bertha Masterstefano when she married and immigrated to America, worked in a lime quarry for Colorado Fuel & Iron and raised five daughters essentially on her own. Every day, I look at their faces in the photo and they give me strength.

My great-grandmother was a working-class woman who never learned to read and write in English and never became an American citizen. Her bravery, accomplishments, and matriarchal leadership contributed to the fabric of this state and this country, but she is exactly the type of person who is often “lost to history.”

In my work at History Colorado, you can imagine that I spend a lot of time also thinking about our community grandmothers – not just about my own familial ancestors. For many of these women, our community grandmothers, we have had to reclaim their stories because documented history excluded, erased, and misremembered their lives.

Here are just a few of the many women in Colorado’s history that you should know. Their lives are a testament to ingenuity, community building, and leadership. The faces of these women and their stories give me strength:

Doña Bernarda Mejia Velasquez was a curandera and midwife who delivered over 3,000 babies in her lifetime. She came with her children to Salt Creek, Pueblo, Colorado, in 1912 from her homeland in Mexico, after serving as a medic for Pancho Villa’s army during the Mexican Revolution. As a trusted healer, she worked alongside doctors as well as with traditional remedies. To support her family, Doña Bernarda was also an entrepreneurial bootlegger and bread maker.

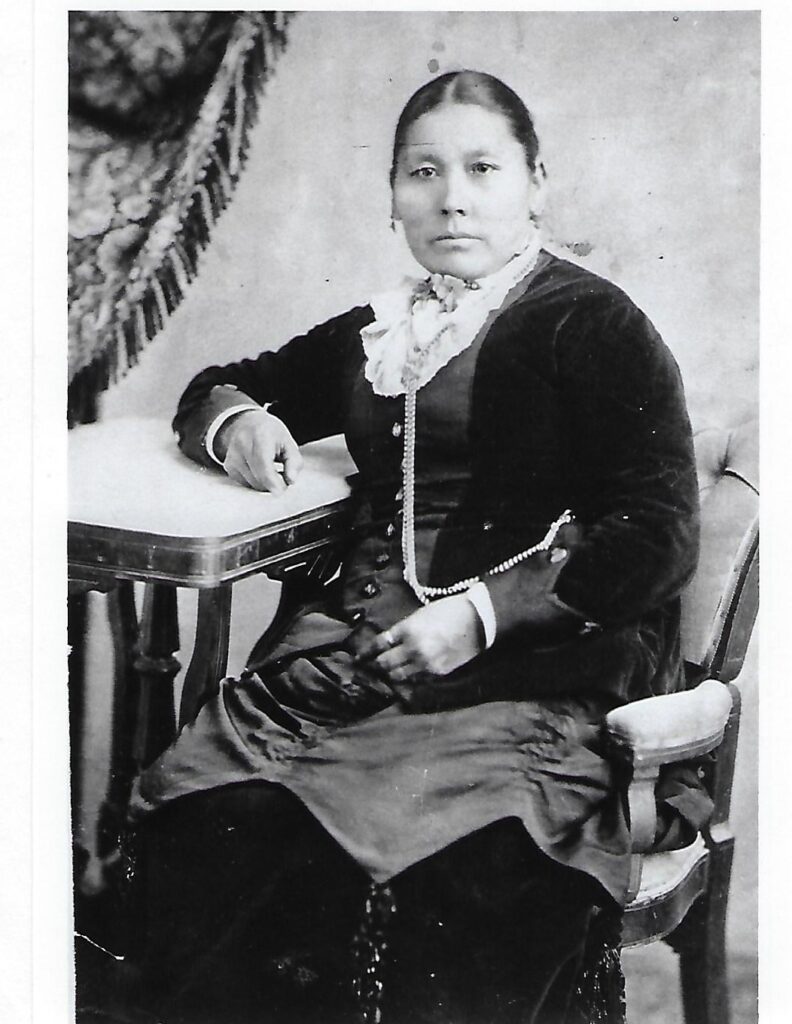

Amache Ochinee Prowers was a member of the Southern Cheyenne Tribe and a business woman along the Santa Fe Trail, who alongside her husband John Prowers, ran an extensive cattle operation and mercantile. She served in many ways as an ambassador among different cultures and shifting empires. She was a Victorian-era wife and mother, married to an Anglo man, who also preserved her Cheyenne traditions in her daily life and in the establishment of her home at Boggsville in Bent County. Her father Cheyenne Peace Chief Ochinee was murdered in the Sand Creek Massacre. Later she received land as reparations from the federal government.

Mary Petrucci lost four children in the 1913-14 Colorado Coalfield Strike, when coal-mining families were forced into tent colonies after striking against companies, like John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s Colorado Fuel & Iron. One Petrucci child died from illness and denial of medical care, while the other three died from suffocating in a cellar under a burning tent during the Ludlow Massacre. Mary Petrucci was with her three children in the cellar but survived.

Wives of striking coal miners, like Mary Petrucci, were active in the resistance against the exploitation of workers and corporate violence. Some women served as union organizers and helped craft labor demands. Many women worked together-across language barriers to ensure all striking families were fed despite meager resources. Mary Petrucci, even in her immense grief, testified to the treatment and tragedies of the strike and Massacre.

Marie L. Greenwood, graduating third in her class at West High School in Denver, enrolled in Colorado State Teacher’s College with an academic scholarship. Despite her academic excellence, she faced blatant racism in her education and noted, “I had graduated with an ‘A’ in student teaching, but since I was the ‘wrong’ color, I was not permitted to teach a single day in Colorado State College of Education.”

In 1938, a few years after her probationary appointment as a teacher in Denver Public Schools, Greenwood became the first African American to receive tenure in the district. As she accomplished new firsts, her goal was to “keep the door open for others to come in.”

As we acknowledge the immense strength and contributions of these women who have formed our state, it is important to ask ourselves: what kind of ancestor will I be? How are we using our strengths and contributions to build a just world for all who come after us?

Let’s make the most of the opportunities that our grandmothers didn’t have to, as Marie Greenwood did, open the doors for others today and in the future.

Header photo caption: (left to right): Esther DiTomaso, Ida Musso, Bertha Masterstefano,

Argie Caporicci, Lena DiPrince, and Ann Musso

Share this article:

Other Articles